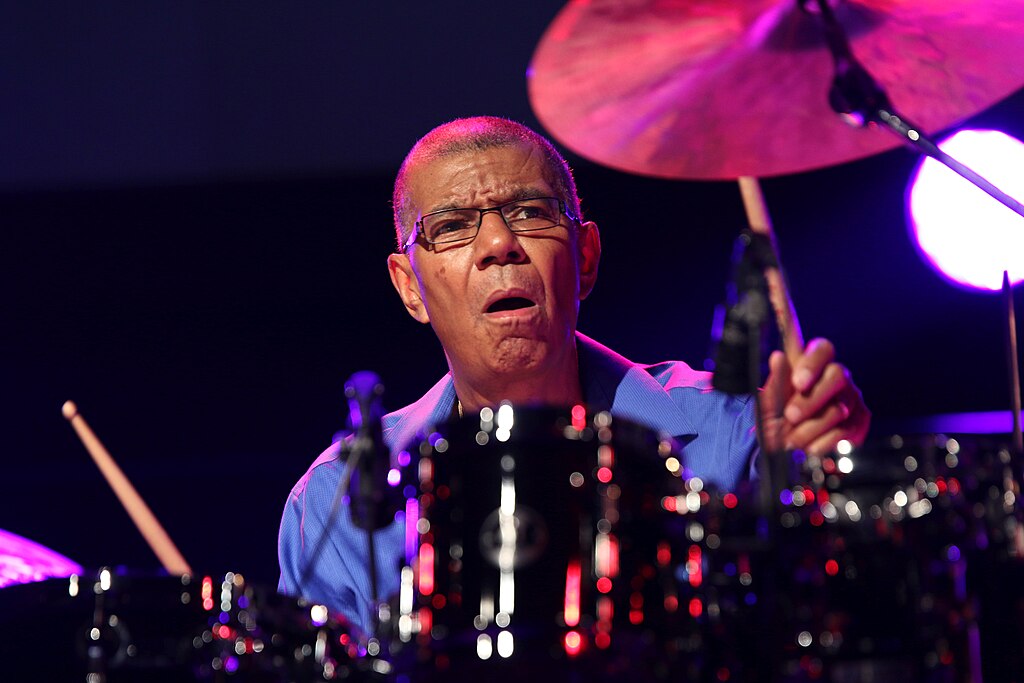

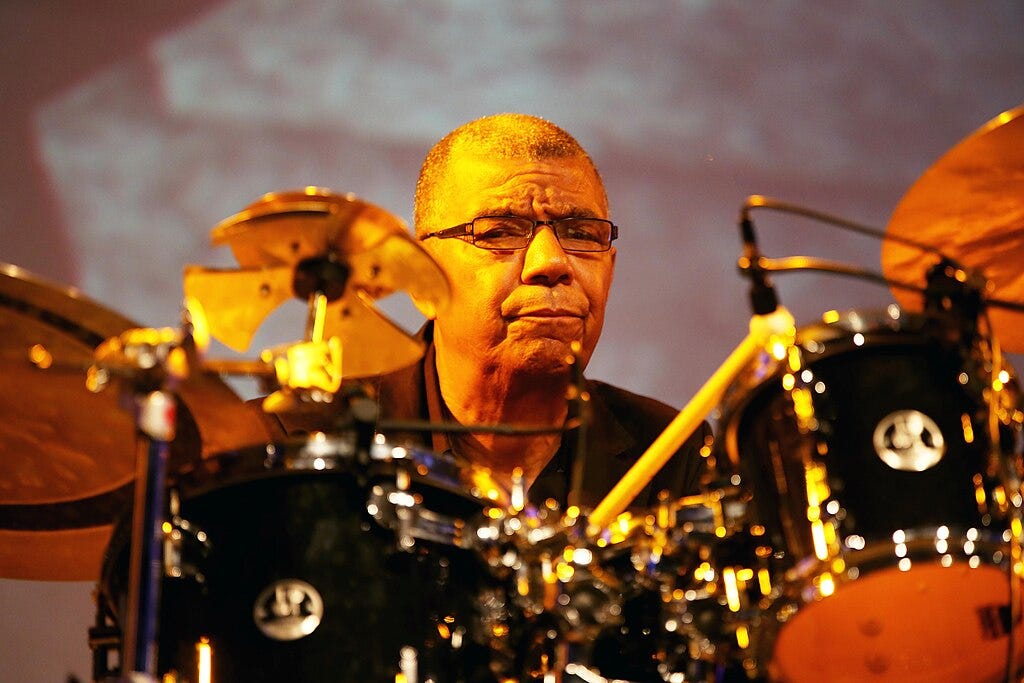

Jack DeJohnette, the critically acclaimed jazz drummer, renowned for his staggering skill and versatility as one of the most prominent jazz musicians of the past 50 years, passed away on Sunday in Kingston, NY.

He played a crucial role in influential bands such as Charles Lloyd’s mid-1960s quartet, Miles Davis’s electrified group in the late 1960s and early ’70s and Keith Jarrett’s long-running acoustic trio. A representative from ECM Records confirmed his death to the Guardian, while DeJohnette’s personal assistant reported that he succumbed to congestive heart failure.

He was 83 years old.

DeJohnette, a Chicago native and two-time Grammy Award winner, began his musical journey as a classical pianist at the age of four before switching to drums while playing in his high school band. In his early years, he was highly sought after as both a pianist and a drummer.

Throughout his career, he collaborated not only with Miles Davis and Keith Jarrett, but also with jazz legends like John Coltrane, Sun Ra, Thelonious Monk, Stan Getz, Chet Baker, Sonny Rollins, Herbie Hancock and Betty Carter. The National Endowment for the Arts noted that he worked with “virtually every major jazz figure from the 1960s onward” and honored him with a Jazz Master Fellowship in 2012.

In a past interview for the NEA, DeJohnette shared his perspective on his talent.

“The best gift that I have is the ability to listen, not only listen audibly but listen with my heart,” he said. “I’ve been fortunate enough to play with a lot of musicians and leaders who allowed me to have that freedom.”

He continued, “I just never doubted that I would be successful at this because it just feels like something’s going through me and lifting me up, and carrying me. All I had to do was acknowledge this gift and put it to use.”

DeJohnette rose to prominence in the latter half of the 1960s, a time when jazz was taking bold leaps in various directions, drawing inspiration from rock, R&B and a medley of global influences while also embracing fearless abstraction. He was part of a quartet led by saxophonist and flutist Charles Lloyd, and along with Jarrett and bassist Cecil McBee, the group went on to become one of the most popular in the jazz scene, touring Europe and performing at rock venues like the Fillmore in San Francisco, where they shared the stage with acts such as Jefferson Airplane, the Grateful Dead and Big Brother and the Holding Company.

His drumming style was a masterclass in versatility, capable of shifting from hushed, intimate moments to explosive, high-energy bursts that could light up a room. The sound of the Lloyd quartet, highlighted in famous albums like the 1967 live recording Forest Flower, which captured their performance at the Monterey Jazz Festival, featured vibrant post-bop, soulful R&B and innovative improvisation. Their music stood out as one of the few jazz recordings from that era to receive extensive radio airplay.

Whether laying down a swinging groove or diving into a fiercely rhythmic pocket, DeJohnette’s work served as a bridge between traditional jazz and the emerging new sounds. His ability to seamlessly blend these elements not only showcased his extraordinary talent but also reflected the passionate evolution of jazz during that era, making him an enormously pivotal figure in the genre’s transformation.

According to The New York Times, DeJohnette’s career took another key turn when he joined legendary jazz pianist Bill Evans and later Miles Davis’s band in 1969. This collaboration led to the influential album Bitches Brew, which marked Davis’s shift into electric fusion. DeJohnette’s performances, especially on Davis’s 1971 album Live-Evil, featured his ability to blend intense energy with a fluid rhythmic style, creating a sound that was innovative yet familiar. Miles Davis noted in his memoir that DeJohnette brought “a certain deep groove” he loved to play over, underscoring the drummer’s indispensable role in shaping the music of the era.

Jack DeJohnette Jr. was born on August 9, 1942, on Chicago’s South Side. He was raised by his mother and later adopted by his grandmother, growing up in a home filled with jazz music from records and radio. At the age of five, he started taking piano lessons on a spinet that his grandmother purchased for him. His uncle, Roy Wood Sr., who worked as a radio announcer and jazz DJ, introduced him to the local music scene and took him to clubs where his passion for music truly developed. A standout moment in his early life was playing the kazoo alongside blues legend T-Bone Walker.

In high school, he sang with a doo-wop group and played the piano, inspired by legends like Fats Domino. But, everything changed when he stumbled upon Ahmad Jamal’s trio in the 1958 live album At the Pershing: But Not for Me. The intricate brushwork of drummer Vernel Fournier captivated him, reigniting his passion for jazz. This newfound admiration led him to explore the genre more deeply. A twist of fate came when a friend left a drum kit in the DeJohnette family’s basement. He embraced the opportunity, playing along with records featuring jazz greats like Max Roach and Art Blakey. In a 2011 interview for the Smithsonian Institution’s jazz oral history program, he fondly reminisced about his journey into drumming, saying, “It took me about a week just to get my independence on the drums; it somehow came natural to me.”

His collaborations read like a who’s who of jazz legends; he shared the stage with guitarist Pat Metheny and formed a noteworthy trio with saxophonist Ravi Coltrane – the son of the iconic John Coltrane – and bassist Matthew Garrison, who is the son of Jimmy Garrison, the renowned bassist from Coltrane’s classic quartet. DeJohnette’s artistic journey culminated in 2016 with the release of his first solo piano album, Return.

Beyond his professional achievements, DeJohnette was a devoted family man, survived by his wife of 57 years, Lydia (Herman) DeJohnette, who not only stood by his side but also managed his career. Together, they raised two daughters, Farah and Minya, and though his earlier marriage to Deatra Davenport ended in divorce, his legacy both in music and in family continues to resonate, reminding us of the profound impact he had on the jazz world and beyond.